Shan Sisi: At the forefront of China’s COVID-19 research

Shan Sisi is a PhD student at the Tsinghua University Medical School and specializes in infectious diseases and immunity. Early during the pandemic she volunteered to support coronavirus research efforts and, after intense work, her small team managed to map the virus protein and isolate more than 200 monoclonal antibodies, making it possible to produce a vaccine. Here she reflects on the work that went into this success, and the stereotypes that she has battled on her way to the laboratory.

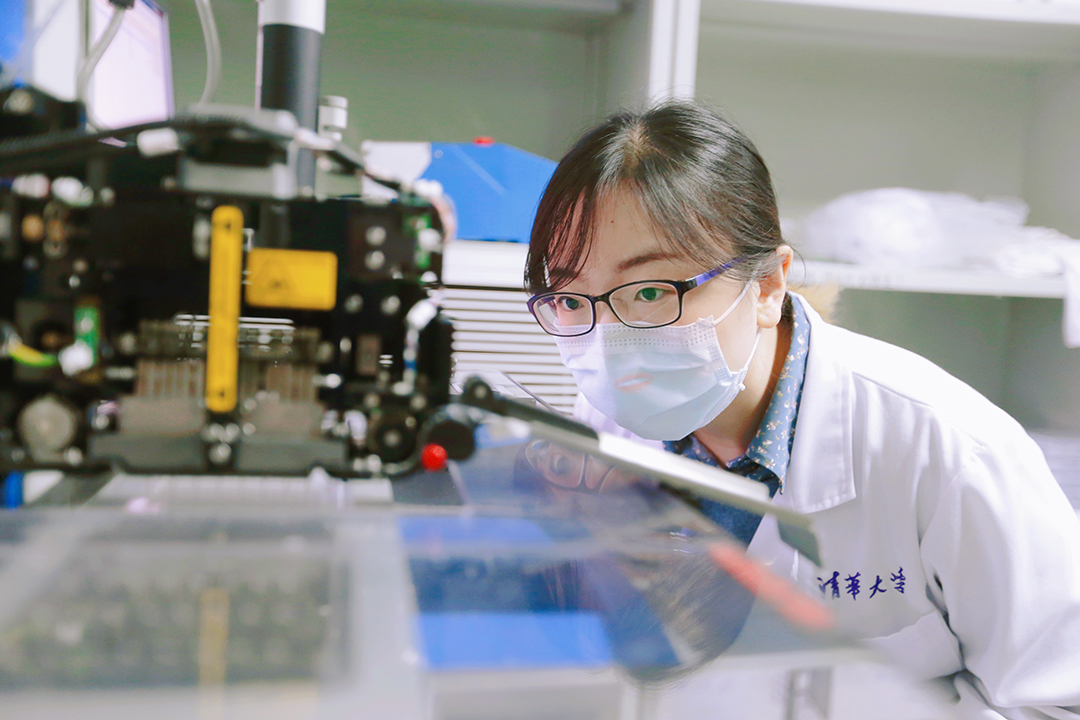

Shan Sisi. Photo: Shan Sisi

"I’d compare decoding viruses to running a marathon. For me it started in 2019 when I heard that Professor Zhang Linqi was forming a research team to study COVID-19. I believed that I had the skills that they needed, and so although I’d only been at home for a day during our winter vacation, I volunteered, changed my ticket and set off for Beijing.

From the moment I arrived, a period of intense scientific research began. Firstly, we needed to solve structural questions about the way that the virus binds to a cell and then uses the cell’s genetic tools to copy and assemble more virus proteins. What we needed to do was to find the right immunity weapons — antibodies. Once we’d found antibodies that could block the virus from entering the cells, we would be able to develop components for a vaccine.

Shan Sisi conducts research on COVID-19 in the laboratory. Photo: Shan Sisi

At the start there was only me and another colleague in the laboratory because Prof. Zhang was quarantined outside of school and other members were unable to return. The combination of an unknown new virus with our small team and intense workload and timeline meant that I’d never faced such a difficult research process! We often stayed up all night, transmitting cells and producing antibodies. Even my new year's eve was spent in the laboratory. But my colleague sent me some homemade dumplings as a Lunar New Year treat, and when I held that warm bowl of dumplings my heart felt full of gratitude and determination – the support of my colleagues kept me going.

By February, other colleagues had joined and we had finally worked out the binding structure. By the beginning of March, we had successfully sorted and identified hundreds of antibodies against COVID-19, working with samples from convalescent patients. Then we began to verify their functions, work with the pharmaceutical industry and test the drug in clinical trials. After several rounds of clinical experiments, we found that the final antibody extracted by our laboratory was effective, even on mutant strains. Of course we’re still working on this, particularly on antibodies for variant strains. This experience has strengthened my determination to serve the public and continue studying infectious diseases.

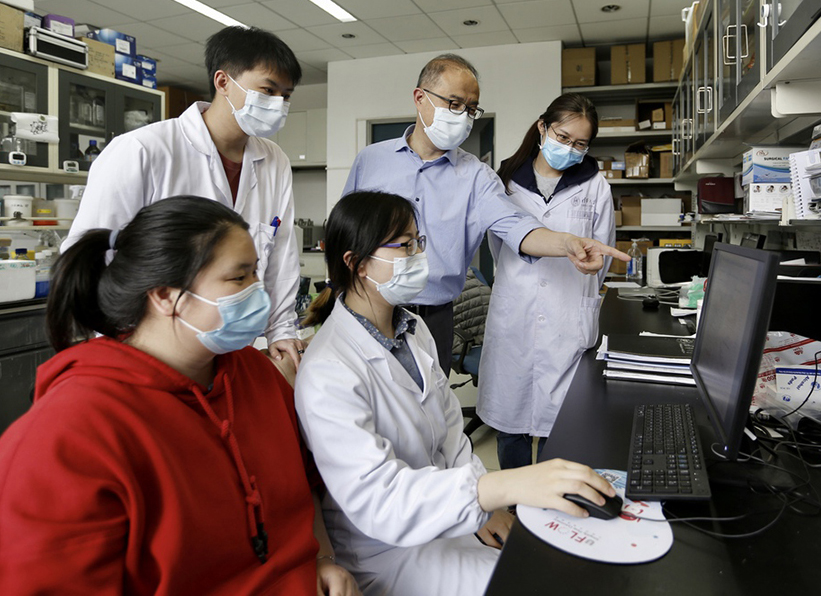

Shan Sisi (front, centre), Professor Zhang Linqi (rear, centre)

and other students in a laboratory. Photo: Shan Sisi

Women are generally underrepresented in scientific research. I have come to realize that stereotypes about women and their behaviour not only have a great impact on their career choices, but create challenges in their work and relationships. For example, men have told me that I’m 'too aggressive' for walking too fast and for focusing on my scientific work.

Boys and girls are assigned roles by society early. I remember that when I was in middle school my class needed to elect two representatives, a president and league secretary. I wanted to run for class president, but school practice at the time was for the boys to be presidents and the girls to be secretaries, so I reluctantly only ran for the league secretary position. When I entered scientific research I knew that women faced more prejudice and pressure. I was able to persevere because of the support and encouragement from family, teachers and classmates.

I want to tell all girls and young women that they should walk the path they choose and try not to be swayed by mainstream gender views, as difficult as that might be! As we grow up, we may witness gender inequality or be treated unequally, and we should learn to try and express our views at this time to make a difference. I also hope to see more and more women joining scientific research teams in the future. This can only create more value for society."